The tilework in the Alhambra of Granada shows us the perfection reached by Nasrid art, whose ornamental and decorative models are governed by constructive principles based on geometry.

Nasrid decoration

Islamic buildings usually have plain and uniform façades, in contrast to the sumptuous and exuberant appearance of their concealed interior spaces, whose abundant decorative details often adorn the entire architectural space.

This characteristic is particularly apparent in the Alhambra of Granada, the headquarters of the Nasrid kingdom, where plain exteriors are accompanied by striking interior spaces. The rooms’ exquisite ornamental details demonstrate the Nasrids’ ability and skill to bring Hispano-Muslim art and architecture to its highest level of development, creating a sophisticated and elegant style that perfected many of the resources characteristic of the Islamic tradition.

The Nasrids remained faithful to this architectural vision, as evidenced by the decoration of the Alhambra, where plasterwork was principally used accompanied by ceramic work and carpentry. One of its main characteristics was its close attachment to geometric, plant and epigraphic motifs, a feature that is largely explained by Muslim resistance to represent animated beings, although the Koran does not however explicitly condemn this practice.

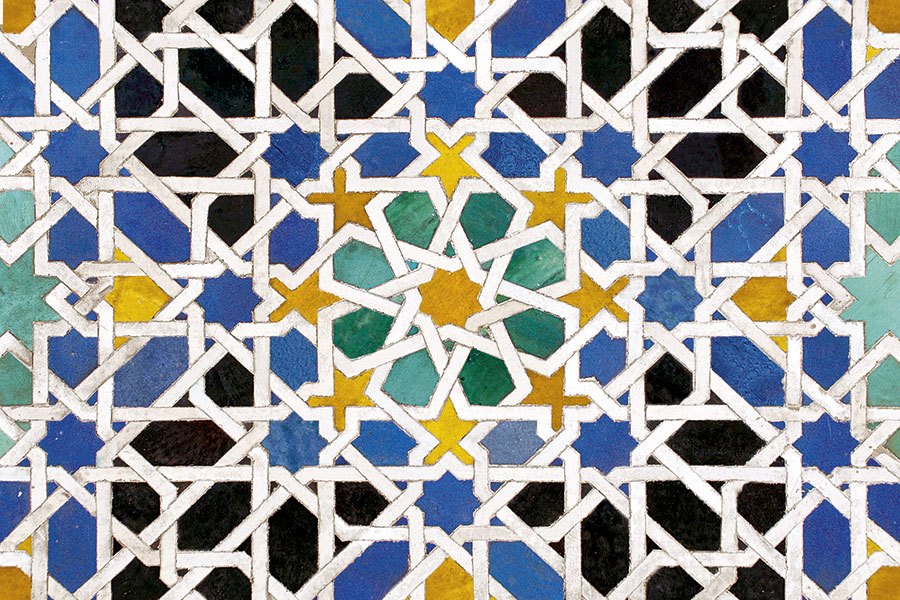

The geometric compositions of Nasrid art are based on the concept of tessellation, that is to say, the covering of the surface by means of figures, arranging them so as not to leave intermediate spaces between them without however overlapping them. The simplest tiling method is to create networks with squares, hexagons and equilateral triangles, which are the only regular polygons capable of filling the entire surface on their own. Nasrid artists often employed this formula to many of their designs, but also devised other more imaginative solutions, subjecting the regular polygons to all types of transformations to obtain new figures with which mosaics, friezes and rosettes and wheels could be devised with patterns that were both sophisticated and harmonious.

The art of tilework

Developed by Muslims in their attempt to emulate Greco-Roman and Byzantine mosaics, the tiling technique consists of cutting pieces of monochrome glazed ceramic using pliers or nippers to obtain fragments of different sizes and geometric shapes –called aliceres in Spanish– which are then put into place like a jigsaw one next to another, following a previously established pattern.

The origin of this type of decoration is somewhat uncertain, though in the 10th century it had already taken root in North Africa. Two centuries later, it reached the Iberian Peninsula thanks to the tribes of Berber origin, although it was the Nasrids who took it to its maximum splendour, as attested by the walls of the different buildings inside the palatial complex of the Alhambra.

Nasrid craftsmen carefully prepared their pigments by using different components of mineral origin which, once blended and fired in kilns, were ground up to create a powder which the ceramic pieces would be coated in.

Tilework in the Mexuar

Refurbished by Yusuf I and Muhammad V over the 14th century, the Mexuar Hall evolved in the Nasrid era around four narrow marble columns that supported a lantern-cupola.

From the late 15th century, with the arrival of the Catholic Monarchs, the Mexuar lost its original layout and underwent great changes so that it could carry out its new role as a chapel. The appearance of the room changed again in the sixteenth century, coinciding with Charles V’s reign, when some plasterwork and tiling were relocated with additions such as heraldic emblems.

In the Mexuar we can find different types of tilework or alicatados. For example, on the lower part of the wall is geometric style tilework that combines pieces that look like elongated stars with small triangular elements that are joined together to form squares. We can also see tracery tilework, with a scheme of black, blue, honey and green ribbons, colours that are repeated on the rest of the ceramic panels that decorate the room.

The paving in the room, refurbished on different occasions, is covered by rectangular-shaped fired tiles that alternate with square tiles adorned with a selection of heraldic emblems, naturalist details and geometric motifs of Muslim inspiration.

Tilework in the Comares Palace

Within the context of the blossoming of Nasrid culture, Sultan Yusuf I promoted in the 14th century the construction of the Comares Palace, which incorporated the elements most characteristic of the residences of al-Andalus, Muslim Spain, and was a true emblem of the power of the Nasrid dynasty thanks to its symbolic decoration.

Practically all the façade is clad in plasterwork, although the tilework also plays an important role in the decoration. In the building we can find tilework framing the doorways and tilework that covers the lower section of the wall.

In the palace interior we can appreciate tilework in the shape of a Nasrid bird in the Court of the Myrtles, tilework in the Throne Room that is based on tracery compositions, and tracery with stars in the Room of the Ship.

Tilework in the bathrooms of the Alhambra

In the Alhambra there were numerous baths, but the only one that has been practically preserved in its entirety to this day is that of the Comares Palace. With a structure that was inspired by Roman baths, the cleansing area was actually divided up into four rooms.

All these rooms were adorned with detailed plasterwork and tiling, but the original iconographic programme was modified after the arrival of the Catholic Kings, who preferred to keep the baths for their own private, exclusive use. In the baths there are original shapes, such as that of the clover, along with other more usual patterns.

Courtyard of the Lions

Distinguished by the fountain that provides the site with its name, this work brought together all the achievements of Nasrid architecture by means of a masterful combination of ornamental elements that helped provide the different rooms in the complex with a refined and elegant appearance, in tune with the functions of relaxation and leisure traditionally attributed to them.

The main room of the palace, baptised as the Hall of the Two Sisters (sala de las Dos Hermanas) has a skirting board that is based on coloured ribbons where the plain coats of arms alternate with those incorporating the Nasrid motto, while the jambs of the arches that communicate with the annexes have wheel pattern tile work that corresponds to the patterns characteristic of the period of Muhammad V.

The Hall of the Kings, on the east side of the Court of the Lions, is lavishly decorated with ornate plasterwork and geometric design skirting boards, while the rest of the walls are decorated with a twelve-pointed black star wheel composition that is based on a pattern comprised of equilateral triangles.

The towers and the Partal

Located at strategic points on the perimeter walls, the towers were an essential element of the defensive system of the Alhambra. Three of these fortifications (the Pointed Embattlements one, the Captive one and the Princesses one) combined their defensive role with residential use. Their spectacular views of the Albaicín and the Generalife coupled with their careful design suggests they were possibly designed for prominent figures of the Nasrid court.

In these towers we find wheel design tilework, pinwheel tilework and ribbon tilework. The Tower of the Captive stands out, with exquisitely designed tilework accompanied by Koranic inscriptions in the main room. In order to compose these inscriptions, the craftsmen had to cut out the blue ceramic letters and combine them with the white pieces that serve as a background.

The book on Tilework in the Alhambra

This book on Tilework in the Alhambra shows the beauty and complexity of Nasrid decorative art. By means of more than 140 photographs, their pages explain the origin of alicatados, how they were manufactured and show the different types of tilework that we can see today in the Alhambra of Granada.

Published by Dosde in a compact and manageable format, this photo book shows the perfection achieved by Nasrid art in the creation of tilework. The book completes the thematic series of books on Seville produced by the publishing house.